The modern Kansas earthquake era looks to be ending

On Aug. 16, 2019, the second day of the school year, students in the Burrton district felt the shake of a 4.2 magnitude Kansas earthquake. They knew exactly what to do: hide under their desks until it stopped.

It was a fairly new procedure, as the district, which is halfway between Hutchinson and Wichita, hadn’t conducted its first drill until the end of the 2018-19 school year.

“They just adapted beautifully,” said Joan Simoneau, the district’s superintendent. “We couldn’t have asked for a better crisis situation, especially on the second day of school.”

Only in the last five years have earthquake drills and damage — one of the Burrton ISD buildings hasn’t been used since August — been a reality in Kansas. A small oil and gas boom dramatically increased the amount of wastewater being injected into the ground, which put pressure on ancient faults.

While experts say the overall trend is declining and the recent spike in earthquakes near Hutchinson shouldn’t last long, some cities are looking for solutions that could lead to more problems.

READ: Kansas set to reopen in phases as some restrictions remain

Under pressure

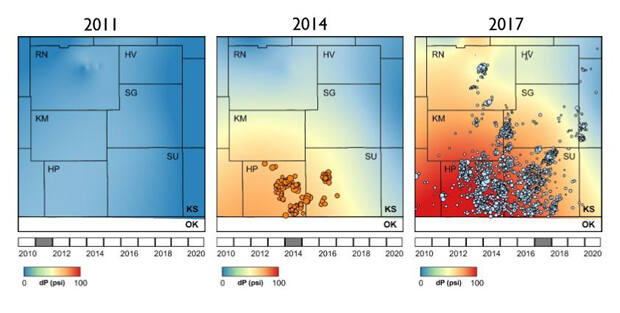

Before 2015, Kansas rarely experienced seismic activity. The faults that existed were minor, with very little external forces acting on them. Then came a rush on oil and gas, thanks to new technology that allowed companies to extract oil and gas from places where it’d been too hard or too expensive. Increased activity meant more wastewater — a lot more.

Shortly after experts linked earthquakes to increased wastewater pumping, state regulators limited the amount of wastewater that could be put into particularly active zones in south-central Kansas.

When oil prices and oil and gas activity all dropped, so did Kansas’ earthquakes.

But the pressure from water injection, which mostly took place in Harper County near the state’s border with Oklahoma, had a long tail, to the point that it’s impacted faults farther north.

“We see a pressure build, we see a direct correlation with seismicity,” Kansas Geological Survey geophysicist Rick Miller told lawmakers recently. “We see a pressure diffusion and now we’re seeing a drop in seismicity, which is really, really, good news.”

RICK MILLER / KANSAS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

There are a few outliers. Hutchinson, in Reno County, saw a spike in earthquakes in 2019. Miller said he didn’t even know there were faults where the main cluster was centered.

The spike also didn’t follow the normal pattern seen elsewhere. When regulators and experts began looking at injection wells in the area, they found that injection volumes hadn’t increased. But there had been bursts, or pulses, of increased wastewater injection in May and July.

Shortly after, Reno County experienced 4.2 and a 4.6 magnitude earthquakes.

“We’ve admonished (well owners) to not pulse, they’ve asked us, define what a pulse is,” said Tom Stiles, director of the bureau of water at the Kansas Department of Health and Environment.

But the connection between pulses and earthquakes is inconsistent, Miller said. In 2016, there were pulses and no earthquakes. The following two years: increased earthquake activity but no pulses.

“… (W)e really don’t have a smoking gun that says this is what caused it,” he said.

A unique problem

The wells closest to the earthquake cluster in Reno County aren’t from oil and gas operations. They’re used by industrial companies and are known as Class I wells.

Hutchinson operates the two highest-volume Class I wells to dispose of the waste produced by the city’s water-treatment plant.

Brian Clennan, the director of public works for Hutchinson, said those disposals are so crucial that “we cannot operate our water treatment center at this point without them.”

The city isn’t just worried about causing earthquakes, either. The space available in well has rapidly decreased; Clennan estimated about only 25 years of useful life left.

To remedy both problems, the city is looking to reduce the amount of wastewater it produces in the short term. But it’s also working on a way to eliminate the need for the wells at all.

One option is to pipe the wastewater into the Arkansas River, which is estimated to cost about $4 million. It also comes with its own set of problems.

The wastewater from the plant is high in chlorides and other nutrients. Put too much of that into the river and irrigated crops will be damaged or killed.

Stiles said the state has been successful in reducing the chloride levels in the Arkansas River south of Hutchinson. And he wants to be extremely careful when considering anything that could reverse it.

“We don’t want to undo some of the progress we’ve made there,” Stiles said. “The one thing we don’t want to do is trade off one set of problems in exchange for another set.”

–Kansas News Service